It Takes Both: Identifying Mano and Metate Types

Dr. Jenny Adams is Desert Archaeology’s ground stone analyst, and is recognized both nationally and internationally as the authority in the field of ground stone technology. This week she talks about the basic tools of food grinding.

When I first learned about manos and metates used in the U.S. Southwest (in the 1970s), I found it confusing that manos were classified according to one set of types and the metates by a completely different set. I learned to give manos type names such as one-hand, two-hand, rocker, cobble, turtle back, loaf, biscuit, rectangular, or ovoid, or to define them by their profile shape or the number of grinding surfaces they had. The metate types I learned included basin, flat, slab, block, trough, Utah trough, through trough, and closed on one end trough. In addition, many archaeologists at that time didn’t use these type names but described the metates they found as Type I, Type II, Type III, and so on, sometimes with subtypes added as Type Ia, Type Ib… There was little point to trying to learn these because they differed with individual projects and couldn’t be universally applied.

At first it was not very clear to me which manos went with which metates. In the reports I read, rectangular and two-hand manos were sometimes assumed to have been used in trough metates, and cobble and one-hand manos were sometimes assumed to have been used in basin metates. In these reports, manos were described as a group, and then metates were described as a separate group, as if they were independent of each other. Rarely did anyone try to figure out which manos and metates fit together as a functioning tool kit. At the time I learned about food processing tools, basin metates were equated with the processing of wild foods and trough metates were equated with processing maize, a new food that was thought to have been adopted in the Southwest around A.D. 400-500. Now we know that maize was grown 2,000 years earlier, when the only processing tools available were basin and what were then called “slab” metates.

So after decades of research and experimentation, here is a short description of what I have learned about manos and metates (see my book, Ground Stone Analysis, for the long version). There were four basic metate types and therefore four basic types of compatible manos: basin, trough, flat, and a type I have classified as flat/concave. The metate types are named for the shapes of their grinding surfaces, no matter whether they were made on slabs, blocks, boulders, or stones manufactured to a specific shape.

Mano types correspond to the metate types in which they were used. Not only that, but a mano is only compatible with (corresponds exactly to) the individual metate with which it was used.

Closely fitting but not compatible trough mano and metate. The width of the mano matches with width of the trough, but the gap between their grinding surfaces shows that they were not used together (photo by Jenny Adams).

Trough manos were not interchangeable among trough metates. The length and convexity of one trough mano will not match the width and concavity of any trough metate other than the one with which it was used. The same is true, if less obviously, for manos used with flat, flat/concave, and basin metates. Manos and metates are paired tool kits, like modern sockets and wrenches.

Now let’s turn to metate types.

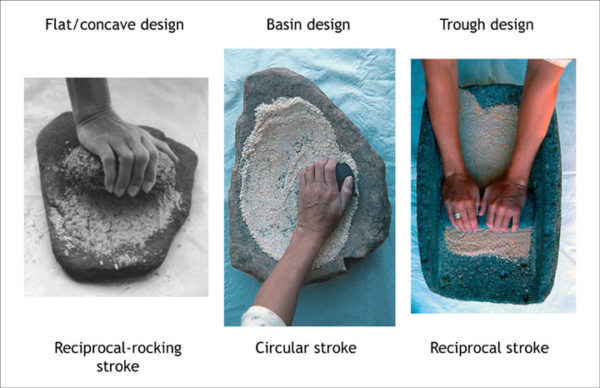

Three types of mano and metate designs. Note that the flat/concave mano is shorter in length than the width of the metate. This photo could be used to argue for the continued use of one-hand and two-hand type names, but one-hand and two-hand mano sizes occurred with basin, flat/concave, trough, and flat manos. My preference is to classify manos by the metate types in which they were used (photos from Ground Stone Analysis, Figure 3.1).

Basin metates were manufactured to have circular or elliptical grinding basins within which manos with convex surfaces were moved, most often in circular or reciprocal (back and forth) strokes. Such strokes wore facets around the perimeters of the grinding surfaces.

Flat/concave metates were designed with flat surfaces and worked with manos that were shorter than the width of the metate. Flat/concave manos were primarily used with reciprocal strokes, with the mano wearing facets into the edges as it was rocked back and forth. Well-worn flat/concave manos have convex use surfaces and their companion metate surfaces are worn correspondingly concave.

At various stages in their use lives it can be difficult to tell apart basin and flat/concave designs, but the important distinction is that basins were deliberately manufactured, while the basin-like concave surfaces on flat/concave metates were slowly created as the byproduct of use. Both tool designs originated during the Middle Archaic period (as early as 3500 BC) and persisted throughout prehistory. Based on experiments, I hypothesize that the basin surface was more useful for confining hard seeds and kernels while grinding, and for juicing stalks or fruits, while the flat surfaces were more useful for working moist or sticky seeds, oily nuts, and working with masa or dough–substances that don’t fly off the flat surface at the touch of a mano or drip away if not contained.

Trough metates have borders that confined ground substances. The manos fit precisely within the trough walls, so their use was only with a reciprocal stroke. This design was first used in the U.S. Southwest sometime around AD 450. Specific trough designs diverged in different core areas, with Hohokam traditions designing metates with a trough open on both ends (called open-trough metates) and Anasazi and Mogollon traditions designing troughs that are closed on one end (called ¾-trough metates). Manos used in troughs of either design became rounded on both ends from rubbing against the trough walls. As the mano and metate wore together during use, the metate surface became narrower and the mano shorter. Sometimes the metate trough was rewidened and the mano was replaced with a new, longer mano, helping to restore grinding efficiency. Trough manos and metates were an efficient change to grinding technology that I think people developed to deal with grinding grains and kernels that had been dried for storage. Their invention coincides with the growing of more floury varieties of maize.

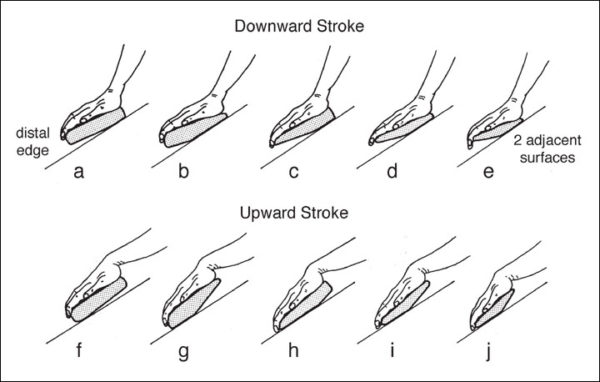

Flat/concave metates are not the same as flat metates. Flat metates were used with manos that were as long as the metate was wide, meaning that as they wore together, the mano maintained a flat surface end to end and the metate remained flat edge to edge. When the metate was set at an angle, the downward stroke of the mano wore a lengthwise depression in the metate surface, but the width of the metate surface remained as flat as the length of the mano surface. As a flat mano became thinner, the grinder lifted one edge to protect her fingers from rubbing against the metate, eventually creating two adjacent mano surfaces.

A significant development in Anasazi food-grinding technology was marked by the placement of fixed flat metates within four-sided slab-lined bins to create permanent grinding stations. These are associated with masonry pueblo construction in the Four Corners area, perhaps as early as AD 900. Within the Mogollon technological tradition, the development of permanent grinding stations occurred later. Instead of bins, Mogollon people built receptacles to contain flour, either by forming adobe collars on the floor or excavating pits into the floor below the end of a trough metate. While slabs were occasionally used in the construction of these stations, they did not form four-sided bins. Receptacles were in use by AD 1200 in east-central Arizona and west-central New Mexico.

Historic Edward S. Curtis photograph taken in 1906 showing four young Hopi women using flat manos and metates in slab-lined bins. Note that the manos are as long as the metates are wide.

Heavily used manos changed in size and surface configuration over their lifetimes, with many becoming too thin to hold. During any grinding stroke, more weight is applied to the back edge (proximal edge), which causes it to wear faster and thinner than the front edge (distal edge).

Mano strokes and the resultant wearing of two adjacent surfaces against metates surfaces (from Ground Stone Analysis, Figure 5.7, drawn by Ron Beckwith).

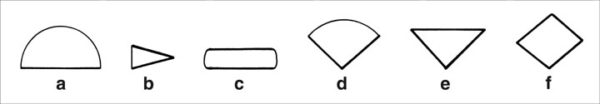

As manos wore, they became less efficient and more difficult to use. The strategies people developed to respond to wear-induced inefficiencies are referred to as wear management. Pecking the grinding surface to resharpen it was one type of wear management. The other two methods of wear management involved deliberate changes to the way the mano was held during use. One of these simply involved using the opposite side of the mano as a grinding surface, as the grinder did not have to stop and resharpen as often when there were two prepared surfaces. The other wear management strategy was to push down on the back edge of a thinning mano and lift the front so that only part of the surface was in contact with the metate. This protected the fingers from coming into contact with the metate surface. If the mano was rotated front to back, two adjacent grinding surfaces were formed. If this was done on both sides of the mano, four surfaces were created.

Looking at manos from this perspective, it’s clear that the shape-related mano types I learned early in my training, such as rocker and loaf, and those classified by the number of used surfaces, were actually classifying wear or wear management strategies.

Location of mano surfaces and as indicators of wear management strategies: (a) one surface; (b) two opposing surfaces created by not rotating the mano against the metate; (c) two opposing surfaces that remain parallel because the mano was rotated from front to back; (d) two adjacent surfaces; (e) two adjacent surfaces and one opposing surface; (f) two opposing adjacent surfaces (from Ground Stone Analysis, Figure 5.12, illustrated by Rob Ciaccio).

Multiple manos would have been used and worn out in a heavily used metate. Whether they were worn out or not, manos were frequently repurposed as lapstones, abraders, and even redesigned into donut stones or hoes. Some heavily used metates have holes in the bottom, but not from wear—rather, the holes were intentionally made as a way to signal the end of a metate’s use-life. Metates were often recycled into roasting pits and hornos as rocks that would hold the heat from coals. I’m beginning to wonder if this was also a form of intentional destruction and not just convenience.

Ultimately, does it matter what terms we use for artifacts? In a word, yes. It is important to standardize the type names we use for manos and metates so that we can be sure that different researchers are indeed talking about the same things (or about completely different things, as the case may be). This allows us to analyze when and where different types of artifacts occur. My colleague RJ Sliva and I recently co-authored a paper in which we talk about the movement of key artifacts around the U.S. Southwest. RJ uses projectile point designs and I use the designs of metates and other ground stone artifacts to model the movements of individuals, families, or small groups. Without standardized, rigorously defined terminology, this kind of synthetic research is difficult to conduct and even more complicated to communicate to other archaeologists. Being on the same page with our words leads to better science.