The Early Agricultural Period Construction Boom

Homer Thiel discusses architecture and recounts the Desert Archaeology investigations he has led that encountered Early Agricultural period pithouses in the vicinity of downtown Tucson.

A construction boom is currently underway in downtown Tucson and in the area west of the Santa Cruz River as new housing and businesses—including the Caterpillar headquarters and the AC Marriott hotel—are being built. A couple of thousand years ago the same areas were the site of a different kind of construction boom, as Early Agricultural folks built houses .

The Cienega phase of the Early Agricultural period dates from about 800 B.C. to A.D. 50. During this timespan people lived on the floodplain along the Santa Cruz River in Tucson, growing maize in irrigated fields. Desert Archaeology has excavated hundreds of houses from this period during work at sites dotting the river’s banks from Ina Road in the north to 29th Street in the south. Although most of these were built in the floodplain, a few houses have been found up on the terrace to the east. Whether the terrace was also a major settlement area remains unknown because it is covered by historic and modern buildings and streets. One of the pithouses we encountered on the terrace has been stabilized and preserved; you can see it at the Presidio San Agustín Museum.

The Cienega phase people built small, round houses. They dug a foundation pit using digging sticks and, possibly, stone hoes, up to 50 cm deep and between three and four meters in diameter. Small postholes were dug around the inside edge of the pit, sometimes placed in a trench. At the Los Pozos site near Ruthrauff Road, ancient house builders placed small bone balls made from deer femur heads at the bottom of a few postholes, probably as some sort of ritual offering. Saplings, about an inch in diameter, were then cut and put in the postholes, and held in place with tamped earth.

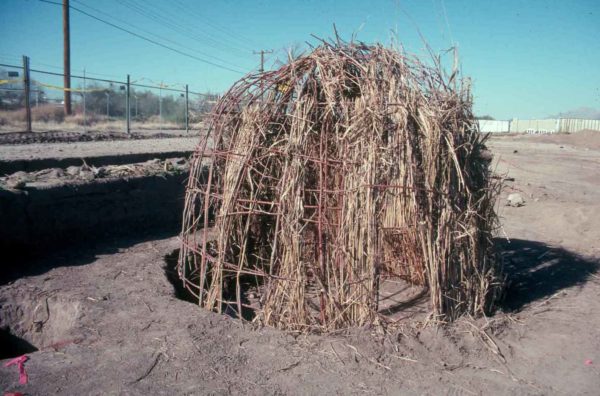

In 2001, Desert Archaeology partially reconstructed a Cienega phase pithouse excavated at the Mission Locus of the Clearwater Site, utilizing the footprint of the excavated prehistoric structure. Willow saplings and yucca leaves were harvested for materials (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

The tops of the saplings were then bent over and tied down to create a dome. Saplings stringers were attached horizontally around the dome, forming a sort of upside-down basket. Then bundles of grass. reeds, or small sticks were woven in among the stringers and poles to cover the structure. Lastly, the builders packed mud on the outside to insulate the house and to help keep rain out, although this was probably not very effective during a monsoon storm. The illustration at the top of this post (by Rob Ciaccio) provides a cutaway view of a typical pithouse, showing the various architectural elements involved.

The partially reconstructed pithouse. Seeds from the Sacaton grass thatching eventually sprouted and grew in the pithouse depression (photo by Robert Ciaccio).

Unlike later Hohokam houses, these structures did not have formal entranceways extending off one side. Instead, an opening in the wall of the house that was covered by an animal hide or a woven piece of matting served as a door. Floors were merely tamped earth, perhaps covered by woven mats. Many houses had small, ephemeral hearths on the floor, usually in the center of the house. An opening in the roof would have allowed smoke to drift out during the winter months when a fire would have provided heat.

Some Early Agricultural period pithouses have pits in their floors. Smaller pits may have been used for storing or concealing possessions. During the Cienega phase, large central pits were used for storing baskets or leather bags filled with maize, both for use as food and for seeds for next year’s crop. Some of these pits are so large, taking up so much of the floor space, that the sole purpose of the house would have been for storage.

Just like today, house remodeling took place. Sometimes a second ring of postholes is present, suggesting a complete house makeover. In other cases, a few random postholes on the floor indicate that extra poles were put in place to hold up sagging roofs.

These structures may have only been used for a season or two, then abandoned, their materials salvaged, and the foundation pit filled in by dirt and trash washing in during storms. Many houses burned, either on purpose—perhaps as a means of getting rid of vermin such as pack rats or mice, or perhaps when someone died (a Native American practice recorded in the Southwest during the historic period)—or by accident, when a spark from a fire lit the flammable building materials.

Photograph of burned posts, stringers, and thatching from an Early Agricultural period house at the Mission Locus of the Clearwater site in Tucson (photograph by Greg Whitney).

Burned houses often have artifacts lying on their floors, things that were left behind on purpose or items lost when the house was caught fire and people rushed out. Some of these items may have been hung from the roof, perhaps stored in woven or hide bags, while others may have been resting on the floor.

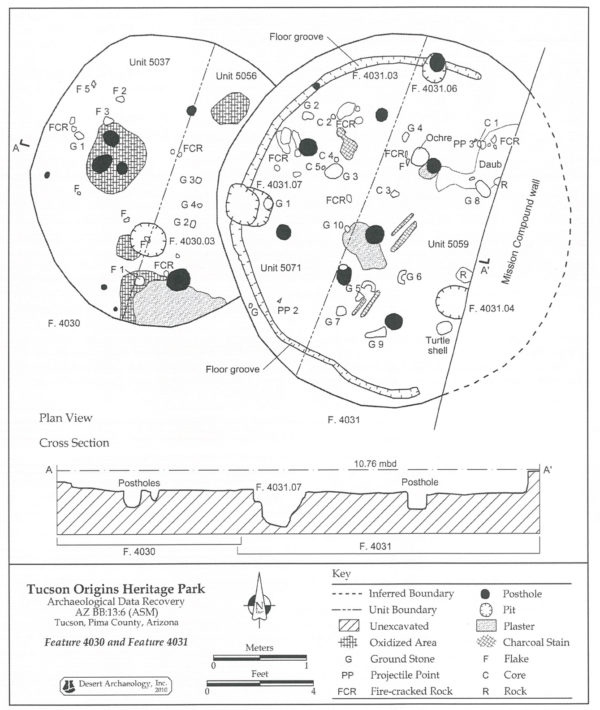

One example is Feature 4031, an Early Cienega phase (800-400 B.C.) burned house found at the Mission Locus of the Clearwater Site west of downtown Tucson. This house was radiocarbon dated to between 758 and 412 B.C. When it was built, it cut through an earlier house, Feature 4030, which had also burned.

Superimposed pithouses at the Mission Locus of the Clearwater site. When the builders dug the pit for Feature 4031 (left), they clipped the wall and dug through part of the floor of Feature 4030 (right), an earlier house that had been abandoned (photo by Homer Thiel).

Desert Archaeology creates maps of each pit house we dig, making it easier to see house structure, understand the placement of artifacts on floors, and relate features to cardinal directions than photographs alone. This map of Features 4030 and 4031 at the Mission Locus of the Clearwater Site was created from a map drafted by hand in the field. The locations of numerous floor artifacts are shown.

When Feature 4031 subsequently burned, a lot of belongings were left behind. When we excavated the house back in 2007, we were surprised at their diversity. A pair of spear points was on the floor and another was found in the dirt just above.

Projectile points found in Feature 4031 at the Clearwater site. On the left are two San Pedro spear points. On the right is a Tularosa Basal-notched spear point, the largest point of Mule Creek (New Mexico) obsidian seen by Dr. Steven Shackley to date (photo by Homer Thiel).

The floor also held five cores (large rocks used as raw material for stone tools), along with a stone hammer or anvil and a few flakes of stone, suggesting that someone was making stone tools inside the house. Eleven pieces of ground stone were present, including a polisher, a mano, a pick, and a donut stone.

Also found on the floor were a turtle carapace (shell) and two lumps of red ochre pigment, once held inside some sort of bag.

These items, and those found on the floors of other houses, help us understand what was happening inside the house and learn about the everyday items people had at that time period. Of course, other things made from perishable materials such as cloth, basketry, and animal hides did not survive.

What is remarkable is that prior to 1994, very little was known about the Early Agricultural period in the Tucson Basin. In that year Desert Archaeology found the first large floodplain settlement to be investigated, located on the grounds of the University of Arizona Veterinary Diagnostic Lab, just west of the Miracle Mile overpass. In the time since, archaeologists have learned much about the people who lived in Tucson during this early construction boom. It is likely that we have a lot more to learn in the future as new modern construction projects require archaeological fieldwork.

For more information (and pictures) about pithouses, see Homer’s earlier blog post covering architecture from the Early Agricultural period through the Hohokam era.